A bruit of wind trumpeted in the man in the hats ears. He had awakened to meddled thoughts, not knowing which were true and which not, the two often interchangeable; a ledger within a ledger. He felt a waning in his neck, where breastplate meets collar, a siphoning of moans and crackles. The sky, as it was wont, was threatening rain, a gray mottle of clouds just above the flap in his lean-to. Today was like any other day, trickery and sham, cold, drizzly bone-gray. He remembered a time when the sky was blue and the rain sweet as candy, syrupy alchemic pulque.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Monday, December 18, 2006

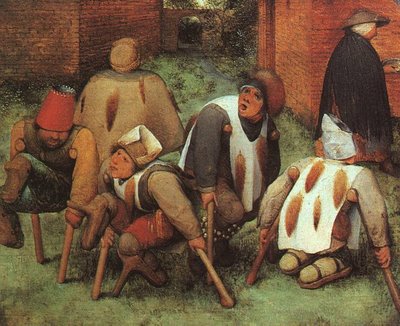

Cajolery and Dumbwaiters

The shamble leg man awoke to a bumping in his head, railheads and tacks jingling and thudding against the inside of his skullcap. This had happened before, after falling into a lamppost, so he wasn’t unduly surprised or taken off-guard. This siege in his head, as he referred to it, was a reaction to night sweats, jimmy-leg and dampness, a cajolery in the distaff of his thoughts, some thought forwards, others backwards and some to the left. He whacked the side of his head, redressed his thoughts, and lit a half-smoked cigarette that looked like a peg. A grey sky hung in his thoughts, a caper backwards and to the left, causing him to feel peckish, sweaty and imbalanced. He recalled running into a beggar who went by the name of the jujube man, as he like nothing better than to suck on jujubes and twiddle his thumb, as he had but one, the other having been sheared off by a cog-pin. He counted out the red ones, as he preferred those to the green, yellow or black ones, and arranged them in even rows at the end of his foot, as he had but one, the other having been axed off by a dumbwaiter.

Friday, December 15, 2006

Thursday, December 14, 2006

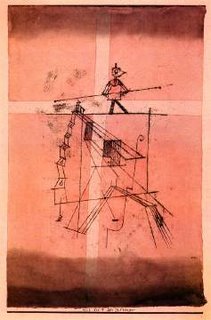

cLAWED tOES

The boy in the hat tipsy-toed onto the rope, nimbly, so as not to snag a golfer’s tack or an untied shoelace, and balanced himself with a rake handle, which he held even with the trough of his pelvic bone. He had read in the back pages of a comic book, where the advertisements for spyglasses and fake moustaches always caught his eye, that expert tightrope walkers seldom lost their balance, as they learned how to hold their breath, breathing morosely through their noses. He wondered why they were sad, and then realized that tightrope walkers, especially experts, had clawed toes and trenches in the bottoms of their feet, from creeping along ropes like thieves, their eyes trained on some imaginary spot in front of them. He checked the rope for tautness, corrected the jib of his belt and practiced holding his breath. He coughed, then sneezed, dry blood zigzagging from his nose, checked his pant’s for the washers he’d put in his pockets to ensure a proper distribution of bodily freight, and checked the rope a second time. He decided to kill a squirrel instead; the one that had built a nest in the elm out of twine and rotting leaves, and was now scurrying along the rope like a defiant child. There was room for only one tightrope walker, as the tautness of the rope could accommodate only eighty-five pounds, so he had figured out with a slide rule and a plumber’s grease pencil, both pilfered from his father’s tool chest that he kept stowed under the workbench in the garage next to his coveralls and a rusty grass scythe.

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

bOX-tWINE*

When the man in the hat was a small boy, a farthing, he had wanted be a ventriloquist. His mother forbade him, saying it was imbecilic, so he took to tightrope walking, the nimble art of heights and balance, long sticks and soft-soled slippers, the sort worn by ballerinas and fancy men. He strung a rope from the porch banister to the elm in the furthest corner of the backyard, jerry-rigged with box-twine and copper brads, and rosined it with dried soap flakes, pilfered from his mother’s washer cupboard. He bought a pair of second hand golfer shoes, removed the prickles with a claw hammer, and rubbed them with otter oil and a damp clothe.

Sunday, December 10, 2006

bALTHUS*

http://www.fondation-balthus.com/

http://www.fondation-balthus.com/Balthus [French Painter, 1908-2001]

• Also known as: Count Balthasar Klossowski de Rola

nATURE'S dISTEMPER*

The shamble leg man awoke ambivalently, not wanting to jump willy-nilly into the day like a walnut-cracker without a pip-splint. His leg, the shambled one, ached and whittled. Perhaps today was a day in between, one of those almost but not quite days that seemed to have snuck into his life like a pickpocket. He patted down the ache in his leg with the heel of his hand and lit a cigarette, one he had snubbed out the night before. His father smoked shag tobacco he swept from the floor of the lunchroom where he worked, the chaff from other’s hastily rolled cigarettes, churned with dirt and oil. The morning sky, in peril of rain, tucked its knees up into its chest and cowered; the threat of hailstones the size of a beggar's ankle-stump, Nature’s distemper and bilge.

Saturday, December 09, 2006

mUD-wAGON*

The man in the hat bought a spoon collection from a fat woman, some with crested handles rubbed smooth and flat; others bent and twisted by a circus strongman or a starving child. Molloy, off-cantor and bilious with ale, his Monteux soiled with mud-wagon, bilge and cockney, trying to dissuade the constabulary from running him in said ‘you dear sire are a dupe, a mountebank and a fool!’ The detective shoved Molloy with the curd of his boot, saying ‘and you, my imprudent man, are a taproot and a burbler, a roughneck and a thug’. Molloy, with ire and scourge, said ‘you and I, we’ll have it out in the parking lot at the A and P, then we’ll see who’s the imprudent burbler, you ass!’ The detective shifted his weight from one boot to the other, his eyes two black smears of anger, and said, ‘milquetoast, burbler, retard, we’ll see, won’t we…yes, so we will!’ Molly looked to the left then the right, sneered at the detective and hightailed it as quick as his imprudence would carry him, bawling, ‘molester, savant, fool, burbler!’

Thursday, December 07, 2006

tHE sPOON mAN*

‘You have a thief’s heart’, the spoon man said. The man in the hat, fingering the loose change in his trouser pocket, replied, ‘and you, sir, are a scoundrel and a Peabody’. ‘You pilfered his hat, you thieving blackheart, the ambassador’s hat, his special official hat, the one he wears at special occasions and to supper.’ ‘I dare say that eating at the soup kitchen is a special occasion,’ the man in the hat said. The spoon man pointed the curd of his finger at the man in the hat, livered with tar and puck, and said, ‘I have spoons you know, a collection, silver ones, some with curlicues on the handles, so don’t push my ire, I warn you, thief!’ The man in the hat cock his hat, smoothing the brim out with a wetted finger, and said, ‘you, sir, are a scoundrel, a mountebank, and I have little time or patience for either.’ With that, the man in the hat turned round, tossed a handful of coins into the spoon man’s hat, and made his way back down the street, the spoon man bawling at the top of his lung, for he had but one, ‘thief, blackheart, Peabody!'.

Monday, December 04, 2006

tINNED sMELTS*

He remembered eating tinned smelts, skin creping from the bone, a bottle of whiskey that came in a wooden box he jimmied open with a pocketknife; shoulder and flank shot with grit, his jawbone working furiously, friar’s toque pulled tight over his head, he remembered these when it rained, or he was too hungry to chase remembering from his thoughts.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

fRAIR'S tOQUE*

A spoiled milk sky, the shamble leg man hovelled under a refrigerator box, cardboard slogged with rain, hands pressed together to form a pyramid, a foil for mizzle and rain. The rainwater sluiced the cardboard eaves, collecting in a puddle at his feet. He remembered buying Indian chewing tobacco, brown coconut clew with sugar, nothing like the chaw his granddad kept in a pouch on his belt, and pretending he was a trapper, feet in mukluks and woolen socks, a friar’s toque pulled tight over his head.

Monday, November 27, 2006

aUTO dA fE*

Mans’ laughter, manslaughter, the man in the hat saw little difference between the two; the one a way of dealing with the horror of the other. The man in the hat had seen his fair share of horror and awfulness, so seldom if ever distinguished between mans’ laughter and manslaughter. He had once be party to an Auto Da Fe where a man was felled at the kneecaps for denying the existence of his poverty, a telling retold with caution and in hushed voices. The harridan told him a story about a dog that had been tortured and left for dead, its eyes yarned with lice and flatworms; stink and fester poaching the carcass, steam rising from the gore. Even though the man in the hat had a weakness for dogs, his stomach churned for the poor beast, evoking horror and disgust, the difference between mans’ laughter and beasts’ slaughter, the awfulness of awful.

Friday, November 24, 2006

cATTERY*

The man in the hat often thought that he would like a chieftain’s hat, a Hetman’s sou'wester with a drawstring and cincher, a measure of his good nature and middling intellect, or simply to prevent the rain from wetting his face. He knew a man, a knockabout, who wore a cane-boater and spoke in tongues, and lived in a trailer near a Babbling brook, or so he claimed. Cane-boaters, or pinpricked fedoras, were not to his liking, as they disproved reason and made one look silly and at odds. Now a Hetman’s sou’wester, bejeweled with baubles and tinkers, was a different thing altogether, something worth considering, if consider at all. A man must take a stand in life, after all, and make the best of a bad situation. He reflected on the assumptions of cattery, thinking that small bonnets or sun visors for felis catus, as the zoological textbook had said, might be worth considering. As he had no preference for cats’ broth, bouillabaisse or chowders, he felt that cattery might be to his liking.

Monday, November 20, 2006

sKINNED kNEES*

These are the days in between, those not quite there days, thought the man in the hat, the wreckage for the future. When he was a boy he would shave sticks into knives, rubbed smooth with tack-paper and sand. His father denied him toys and little things, so the man in the hat made his own, fashioned out of wood and paper, nails and brads, whatever was at hand and within reach. He smoked twigs and braids of grass, anything that could be lit and kept so. He hid behind the garden and smoked until the tuck of his lungs ached and his face turned red, thinking of ways to escape the past, forget the present and dream up the future. He remembered skinning his knees or bumping his head, casualties that only little boys remember, and his father’s vacant stare, lost in his own sadness and despair. When he grew taller than the pencil marks on the doorframe, the man in the hat left home, leaving behind his father’s vacant stare, rubbed sticks, and memories of skinned knees and bumped heads, a childhood spend hiding behind the garden shed, the days in between, the not quite there days.

cOWSLIPS aND dAFFODILS*

The shamble leg man gave her a gift of flowers, cowslips and daffodils, a nosegay of peonies and chrysanthemums cinched together with a bootlace. She put them in a Gin bottle, stopped the neck with a trackman’s stub and opened her legs, a boar of pubic hair caught in the elastic of her underpants, red blotches where cockroaches had eaten soft tissue, and a Rorschach birthmark, the one identifying mark that made her, her and not someone else.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

nYLON, fLAY aND sKIN*

She soaked her feet in Epsom salts to encouraging blistering, and to harden the callus that grew like scats on the heels of her feet. Her toenails curled up at the ends like birds’ talons, yellow shale, sharp and cetaceous. The barbs and hooks gibed her stockings, tearing through nylon, flay and skin.

Monday, November 13, 2006

Saturday, November 11, 2006

dEFIANT rEASON*

She kept her thoughts in a casket with a bird’s foot and an ostrich feather. The man in the hat awoke to a sky blistered with rain, smoke trailing from a half-spent cigarette left smoldering in the ashcan. He scooped his hat from the floor; weevil-wood cursed with scuffing, and re-lit the nub of the cigarette with a struck match. He smoked in defiance of reason and common sense, the bellows of his lungs heaving, breastbone cockling rib-stays.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

tHE sKY iS fALLING*

‘The sky is falling, she said. ‘How can I be expected to make a living in such horrid conditions?’ The harridan sat under a curd of lamplight knitting the hem of her dress with chopsticks she had found behind the Chinese grocer’s, next to a placenta of bock chow, fingers pearling, eyes cast into the hollow of her brow, sticks clacking against metal shims. The harridan cocked her head, her neck spidery and variegated with loose skin, and stared into the sun, her eyes squinting into the hoar. The sun scalded her face; a face sallow and bricked with age, and bellowed into the crop of her ears. When she was a child she stood for hours in the hot sun, her face a cowering glissade of red skin and tuck. She thought of marigolds and peonies, her father’s arm slung out the car window, his cigarette threading a blue line of sky, and her mother’s dower face crinkled with distemper and bile. She slapped her with the back of her hand, the one she wore her wedding band on, leaving a red line on her cheek, her eyes watery with tears and murder. She called her a little cunt and made her stand in the corner, her nose pressed into the bricks, mortar bleeding into the pall of her face.

Monday, October 30, 2006

Saturday, October 28, 2006

sALT-tONGUE aND sHAG*

A pork gray autumnal day, it was, boiled beyond recognition. The sky is the simmer, the effluvia that scum’s the top of the boil. The man in the hat fixed himself a plate of dogs’ meat, skewered with onions, carrots and garlic, and forked it into the gutter of his mouth, a crisper of teeth and salt-tongue. He chewed the meat with great relish, his teeth clacking against the cod of his tongue, blistered with lesions and scabbing. He washed down the meat, a pulpy mash of tissue and sinew, with a mouthful of Marker’s Port, wiping the crumbs from the fop of his trousers with the heel of his free hand. He rolled a cigarette from shag and flake, ends and bits, other’s castaways wet with slaver and spittle, and sucked hard on the bitter root. Should the harshness of the roll embitter his throat, he would suck harder, drawing the smoke through the warren of his nose, a cudgel reddened with intemperance, wind and atman Sherry. Today was yesterday, tomorrow today, an endless beginning, a whole through which one crept, cursing the indifference between the two.

Monday, October 23, 2006

tINSMITH'S aWL*

She hiked her skirt up over her thighs, scabby and red with blotches, and rearranged the ribbon in her hair; a red and blue one with a tinsmith’s awl pinched the bow. ‘These are sad times,’ she thought to herself, ‘sad indeed.’ She inspected her feet, shod in Rubbermaid sandals, someone else’s castaways, and smiled, ‘sad times indeed.’ ‘Should the sky fall in I wouldn’t pay it any notice’, she thought, ‘as skies are interchangeable and nobody’s business, not even mine, were I to bother, which I never will’. A gull biffed across the top of her head, feet flapping against the bow in her hair, cackling like a barn cat, a cigarette butt twisted into its beak. She threw her hands up over her head and bawled, ‘away from me you fucking rat, haven’t you anything better to do than muss the bow in my hair?’

Sunday, October 22, 2006

lEPROSARIUM*

A gray simmering day, cloud bursts and a colic of rain and marrow, such is the day, the man in the hat supposed, a boil in a same such pot. No, the sky is a leprosarium and each cloud a severed limb, a necrotic fall-away; each nose, finger, joint, a reminder of nature’s un-heavenly authority, rot and blister, a graveyard of molt and scurvy. The beggar woman harried behind the Post Office, lifted her skirts and peed; a cockscomb of urine jangling against the brickwork, her eyes pressed tight, a rifling continence. When she was a girl, a farthing child, her mother slapped her cheek for urinating in the park, her skirt pillared with urine, the sky a robin’s egg blue, so she remembered. Her father, whom she seldom saw, was busy living out his misery in a rooming house drunken on pot wine and Listerine. She imagined her life as a circus, clowns and freaks, a boy who looked like a dog, a woman with a beard, a strongman with bumpy arms, children sucking on cotton-candy and caramel-apples, and her father swigging pot sherry from a plastic cup, his eyes crossed in on themselves, a nose like a pared carrot, a fancy woman at his side.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

tHE bOY iN tHE hAT*

Could there have been a boy in the hat, well of course, yes indeed. As all men in hats are preceded by boyhood, it seems reasonable that a boy in a hat precedes a man in a hat. There is a natural regress that starts from birth and ends with demise, the cessation of breath and life; in between conception and demise lies the in between, the place where hats and umbrellas exist, the place of beginnings and endings. So it stands to reason that the boy in the hat preceded the man in the hat, a natural regress from beginning to middle to end. Remember, if you recall, that I am simply remembering this for someone who wishes to remain anonymous, without beginning, middle or end. In this manner, and this manner alone, regress and progress are one in the same, cut from the same broadcloth, so to speak, and can be interchanged with one another with grammatical impunity.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

tAILLESS kITES*

A blue sky crouching in the barrows of a whore’s skirts, some skies are different than others, mused the man in the hat, a faint simulacrum of sky, a sky within a sky, a skinless sky. Clouds were the god’s way of inducing order into the disorder of skies, a way of making sense of cobalt and cerulean, gunmetal blue and Prussian, indigo and azure blue, blue, so he thought. Umbrellas were useless things, he considered, especially when used to ward off rain and hail from the clutter of one’s head. Hats were much less cumbersome, as they required little property or use of one’s hands, thereby allowing for free access to things and people that lay in one’s way, such as alms men and harridans, and men with shamble legs and three-legged dogs with mange and cockle-eyes. Walking is less enjoyable, he concluded, when the umbrella, which is nothing more than a coleus of twisted spokes and battened cloth, had to be manhandled into submission, an unruly kite with an equally unruly tail. He much preferred the simple hat, a boater or a fedora tarweed with oilcloth, quid into place with scotching or a safety pin, to the umbrella, which was nothing more than a vexing encumbrance, a tailless kite with little regard for one’s desiccation or wellbeing.

Saturday, October 14, 2006

sAD sORRY bASTARD*

‘You’re a sorry bastard,’ he said. ‘I seen you ripping other guy’s stuff off, like they’re shoes and hats, stuff like that, I saw you doing it behind they’re backs when they was asleep or looking the other way. You’re a fine one, you are, a real champion, a fucking all-time champion. Stealing when they weren’t looking, behind they’re backs, when they was asleep or looking the other way. Sad sorry bastard, that’s what you are, an all-time champion bastard.’ The alms man patted his trouser pockets for a match, screaming in defiance of fire and sulfur, tobacco, the morning sky, ‘for the love of it, I can’t go on, not like this, without a matchstick or striker.’ The sky opened its great maw, jacking rain and wither-leaves into the still morning air, nature’s distemper and fury. The alms man shifted his weight, the seat of his trousers scouring the sidewalk, and closed his eyes, ‘this is how I live,’ he said, ‘like an animal, a brute, such unreason and belittlement’.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

wHEY mARROW*

A cooper brown sky, a menace of rain, a pilfering; such is how the day began for the shamble leg man, against his will and judgment to the contrary. Soon the leaves would be oven-ready, kiln dried and crumbled, a crematorium of wither and decline. Sheep queued to the slaughter; such were the clouds that curded the sky, whey marrow, ox-mallet, throat-slitters, mincemeat for the soup kitchen and Waymart, spoons clacking, tabletops dross with spittle and throw-up.

tHE cOMMON gOOD*

The alms man lived in a world of ought to’s and oughtn’t, and as he felt that the two were synonymous, doing one or the other amounted to the same thing. He, the alms man, had deducted an ethic of ought to, doing away with moral imperatives and duty. Judgments were reserved for common things, food and potables, where best to sleep or how to steal something without getting caught. Anything beyond these were deemed secondary, collateral to the common good, which was the good that was common to him and him alone. Not common goods shared in common, but rather discommoded goods for the common good of one person, the alms man. For example, a curd of day-old bread, a rye or pumpernickel, lets say, was considered good for just one person, and in this way a common good for the good of the one person, a goodness common to the greater goodness of one person in common with himself, the alms man. In this manner the ought, any ought, was a common ought, an ought to common to one person in common with himself. The alms man, being in common with himself, and thereby in common to himself and himself alone, was actually a good unto himself, a common good synonymous with the greater good, which was a common good in common with the good of one person, the alms man. Anything beyond that was uncommon and secondary, a collateral good that was no good at all. The alms man had this all worked out on an abacus he had found in the rubbish behind the Sears store behind the Waymart next to the alleyway that led to the Mercury Fish Company, and with a pencil he had pilfered from the Five and Dime on a Saturday.

Sunday, October 08, 2006

a lEITMOTIV fOR nOTHING*

Much as I might, I will never understand the world, its comings and goings, all this frittering and lolling about. Perhaps these are things not to be understood, to be restricted to common sense and reason, but a measure of the bifidity of the world, its wont for order and coherence. One end appended to the other, a caudal disaffection, a theme without a variance, a leitmotif without a motif, a buckling in on itself, an implosion of order and common sense. Why but why, he asked himself, the alms man did, do things happen when they shouldn’t? Why it is that one thing is another and another, another? Perhaps my judgments are buckled, falling in on themselves, a leitmotiv for nothing, a frittering about.

Saturday, October 07, 2006

cATS aND dOGS*

A yellow surgical antiseptic, for the prevention of fester and septicemia of the glottis, this is how the evening sky represented itself to the shamble leg man. Why, he thought, is it that cats are not dogs and evening skies are never the same twice? Why does the sun shine on a cloudy day, and why does one tree grow taller than another? Where is the logic and reason in this, he thought, the cause that never seems to have an effect? Why such hooliganism and irreverence, when a simple nod of agreement would suffice, even were one’s head blain with tics and lice, or the sky looked the same twice and one tree grew just like another? The senselessness of it all confused him, addled what little thought he had, what few moments of clarity he was capable of riving from the scullery of his mind. This is absurd, he thought, absurd indeed. Who lives like this, he mused, with such mean spiritedness, such improper reasoning, a fool, a coward, a dilettante, no less. This thinking is foolish, not worth the time and bother, he thought, against his better judgment, against his desire not to think thoughts. I will be done with it, he exclaimed, be done with it for good. I have better things to do, after all, things that have a purpose, a meaning, have some reason and sense, make sense and have a sense of common sense. He struck his leg against the curb, his ankle buckling into the harp of his foot, and proceeded up the sidewalk, his face trove and addled with improper thoughts, thought by a dilettante, a coward, a common fool.

Friday, October 06, 2006

tHE oTHER mAN iN tHE oTHER hAT*

The man in the hat met another man in a hat, a Papal circlet with a quail’s feather in the hatband and a cross pinned to the brim. He, the man in the hat, asked the other man in the other hat why he chose a hat that looked more like a miter than a common hat, such as the fedora or the panama, or the top hat or the bowler, or the woolen toque, which, he added, is common to knockabout’s and bootblacks. The other man in the hat, the circlet hat with the quail’s feather and cross, said, after clearing his throat through his nose, ‘because I am the king of my kingdom, the fief of my fiefdom, lord and master of my sovereignty’. ‘I see’, said the man in the hat, and continued on down the sidewalk, his gamy leg trebled into his trouser leg, his hat, the gray felt fedora, tied round his chin with a length of child’s string, in case a bluff of wind or a shim of gelling came caroming into his head, or it rained like Noah and Lot, in which case he would affix his rain-cap to his fedora with a scotching of tape and a pin, which he stowed in his pocket just in case such a chance of happenstance were to occur, which it might.

Monday, September 25, 2006

sPINY sTEM pIECE*

The morning sky was as black as a murder of crows, so the man in the hat chose a rain cap and an umbrella with a spiny stem piece that fit firmly in his hand. He walked out into the rain, overstepping a puddle that had formed in the night, and struck his leg against the wet pavement. He kept his gamy leg at a distance from the good one, to discourage a conspiracy, which he knew from experience would result in a twofold limp. The sky opened up its great maw and shouted rain, the string he used to fasten his rain cap around his chin cutting into the goiter of his neck, a drizzle of spout rain, which had collected on the roughing of his lean-to over night, splashing into his eyes, his nose and along the cove of his face. Today is no different than the one that preceded it, he thought, no better, no worse, just a continuation of one unprecedented daylong day. When the day’s lost they’re precedence, the man in the hat knew that the night would soon follow, then the in between times, hours, minutes, seconds and then the whole thing would collapse in on itself, creating a void, an emptiness where space and time and matter should be. This thought saddened him, but not enough to set a precedence of sadness and negative thinking, no, those he left to the alms woman and the shamble leg man, for they knew no better and couldn’t be expected to think otherwise.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Monday, September 18, 2006

pENCILS aND hAWSEHOLES*

‘What’s the bother, man, seems to me you got your hat on back to front, silly fucker’. The shamble leg man frowned and laid his hat on the pavement next to the clochard’s alms cap. ‘Silly, silly fucker, you are, damn right, I’d say’. The shamble leg man took a pencil from his inside coat pocket, sharpened to a fine point with a paring knife, and smiled. He raised the pencil, pointing the sharpened end at eyelevel with the clochard, and smiled again, this time with a sneer hidden beneath a masked indifference to beggars and silly fuckers. ‘We’ll see who the silly, silly fucker is,’ he said, raising the pencil over his head. The clochard, now aware that his invectives had drawn out the worst in the shamble leg man, his ire and discontent, swung his left leg over his right and pushed his alms cap under the seat of his trousers. ‘If your going to poke me, ‘he announced, ‘best do it quick, cause if I catches your arm, I’ll drive that silly pencil up your fucking hawsehole.’ The shamble leg man turned to fact the clochard head on; his eyes two black beads in the clove of his brow, and smiled, this time with teeth brown and rosined with tobacco chuff and Catholic Porter, ‘give way,’ he said, ‘or I’ll be forced to give you the give way.’ The clochard raised his hand, a briar root twisted into a scout’s knot, and smiled. ‘You think you’re the only one with a pencil?’ he said, eyes trained on the Shamble leg man’s raised hand, the brim of his alms cap sticking out from beneath the seat of his trousers. ‘If worse comes to worse,’ the clochard said, ‘I’ll kick the faith right out of you, then steal your wallet and hat, even though I find hats, yours in particular, abhorrent.’ The shamble leg man pocketed the pencil, pulling the lapels of his greatcoat tight round his chest, and smiled, his eyes black with hatred, sockets bloodied with disgust, and turned up the sidewalk, the clochard yowling after him, his cap vacant of coins and alms.

Friday, September 15, 2006

tHE lEDGER-mAN'S dAUGHTER*

The alms woman awoke to a gray marrow sky; striking a match against the Braille of her foot, she lit a half-spent cigarette, took a pull on the brown filter, and exhaled a plume of blue-gray smoke. She had slept the sleep of the restless, awash in a dreamscape drone with faint whispers and muttering. Her memories, those she still had courage to remember, were of beatings and humiliations, of nights spent in a hovel, legs cloven beneath her skirts, a buzzing in the hollow of her ears. Her father, when not laboring over tallies and ledger entries, ate pigs’ tails and tripe, washing down the placental mush with brown ales and porter. He seldom spoke to his daughter, and when he did, with a voice that boomed off her chest like a mortar rocket, his eyes bloody with missed opportunities and hate. Since the untimely passing of his wife, the alms woman’s mother, he took to hatred and drink like a man bent on destruction, his own, and anyone within striking distance of his distemper and brutality, a carnage of broken bones and faces reddened with the back of his ledger-man’s hand. The alms woman retreated into the tally of her own thoughts, a place of fear and cowering, where she found little solace in the thought that once he was dead, she would be freed of his cruelty, his need to destroy the things in his life, those things that once held meaning and purpose, existed outside his hatred of them.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

tHE aLMS wOMAN*

The shamble leg man took a sulk off his cigarette, smoke issuing from the hole in his face, his eyes squinting to make sense of things. He seldom made sense of things and preferred it that way, as it made his life simple, less ambiguous, easier to mind and tolerate. He knew the alms woman, having met here at a rally for the homeless and destitute. He knew all too well that she kept a paring knife beneath her skirts, sharpened to a fine edge on the strop of her leg, where the skin was leathery and tough, a graft of stitch marks and scaring, tissue crosshatched and serrate.

oVEN sPOIL*

These are the words of a madman, lunacies. A life not quite lived, a lifeless life. A gamecock held aloft in a whetstone hand, rubbed raw and scalloped with spoil and labor. A man in a wide-brimmed hat, legs gamy and spurred, tendons knotted into a toreador’s bolo, gamboling step by step into the fetter of night, marked by irrational distortions and stuttering. These are the thoughts of a madman, a lunatic, head cupped in the palms of down turned hands, a fretting, a gibbeting, a ferric alchemy of slag and oven spoil.

Thursday, September 07, 2006

tHREADWORMS*

Having teeth is a pleasure, one not afford to threadworms and the downtrodden. The alms woman, though not a threadworm, has acquired threadworm characteristics, a needling unsettledness, a poaching, a refried beanery of bland foodstuffs and mouthwash. She is connected to disconnectedness, to a nothingness, a barely anything emptiness, a nonbeing, a being nothingness. All being is being becoming nothing, a becoming nothing, a nothingness of being. We never are, but are always becoming, coming into being and nothingness, a nonbeing, a being of nothing, nothingness of being, a nonbeing nothingness of being, nothing.

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

sLOUGH aND bREAD*

The man in the hat met a woman, a harridan, who had in turn met the shamble leg man, all three having met each other unbeknownst to the other. The man in the hat met the harridan, the woman, while out strolling, ambling up sidewalks and down alleyways, through tiny porticos and lanes no bigger then a wren’s neck. He noticed her out of the side of his eye, a washerwoman in her slough, crouching amidst the workaday hustle and bustle. He approached, his gamy leg weakened from ambling, and stood to one side of her, not wanting to upset her or cause a kafuffle. He knew from past experience that a street hag, a harridan, with stump-worn teeth and an alms basket was not someone to be trifled with, a person not to be pushed beyond reasonable limits, whatever those limits might be. ‘Might I have a minute with you?’ he inquired, the woman shifting her weight, palms wrenched into the asphalt for leverage. ‘Why not?’ she said, eyes trained on the man in the hat’s walking stick, waiting to see if he might not shift his own weight from one foot to the other. 'This might sound odd and insincere,' he said. ‘Yes, if you feel the need to, yes, go ahead, yes’ the woman said, the palms of her hands hidden beneath the barrows of her skirt. ‘Could I buy you some teeth, dentures, perhaps, new ones?’ The man in the hat, fearing a reprisal, or worse, a sound beating, swung his walking stick across the front of his chest and shifted his weight from his bad leg to his good one. The woman, the washerwoman, pulling at the hem of her skirt, a thread having come loose and unraveling into her lap, smiled, a black hole where whiteness should be, and said, ‘why the hell not, these ones aren’t worth a crock. Can’t even chew a heel of bread, alignments all off.’ She pulled her hands from beneath her skirt and stuck them out, palms up, fingers twisted like briar root, and added, ‘and what’s left of them ain’t much good neither.’

The man in the hat reached into his greatcoat pocket and retrieved his billfold, out of which he took a white card with the name, address and phone number of a dentist, not his, but someone else’s, someone he once knew, was acquainted with, but knew no longer, had become unacquainted with. ‘I’ll make an appointment for you,’ he said, holding the card out for her to see. ‘I don’t need a checkup,’ she said, her hands receding under her skirt. ‘No,’ the man in the hat said, ‘I’ll make an appointment for you to get new teeth, dentures, perhaps.’ ‘Oh,’ she said, ‘new teeth, dentures, I see, yes, go ahead, yes.’ The man in the hat replaced the card in his billfold, gingerly closed it, and slid it back into the pocket of his greatcoat. ‘I’ll come by, say next week, same time, and give you the money for the teeth, dentures, whichever the dentist thinks is right for you.’ The woman smiled, a Black Cat chewing gum smile, and curtly waved him off, as the office building across the street was emptying for the day, and the woman, the very same one who had once met the shamble leg man, didn’t want to miss the opportunity to fill her alms basket to overflowing with coppers and cheap silver coins.

The man in the hat reached into his greatcoat pocket and retrieved his billfold, out of which he took a white card with the name, address and phone number of a dentist, not his, but someone else’s, someone he once knew, was acquainted with, but knew no longer, had become unacquainted with. ‘I’ll make an appointment for you,’ he said, holding the card out for her to see. ‘I don’t need a checkup,’ she said, her hands receding under her skirt. ‘No,’ the man in the hat said, ‘I’ll make an appointment for you to get new teeth, dentures, perhaps.’ ‘Oh,’ she said, ‘new teeth, dentures, I see, yes, go ahead, yes.’ The man in the hat replaced the card in his billfold, gingerly closed it, and slid it back into the pocket of his greatcoat. ‘I’ll come by, say next week, same time, and give you the money for the teeth, dentures, whichever the dentist thinks is right for you.’ The woman smiled, a Black Cat chewing gum smile, and curtly waved him off, as the office building across the street was emptying for the day, and the woman, the very same one who had once met the shamble leg man, didn’t want to miss the opportunity to fill her alms basket to overflowing with coppers and cheap silver coins.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

pADDY'S sTOUT aND lAGER*

These are the sorts of things that make life a carnival, a Dervish whirling out of control. Why, the man in the hat thought, do people drag dogs on tethers, poor creatures, and wear uncomfortable shoes, and hats crêpe and bejeweled with baubles and string? Why so much of so little and so little of so much, he thought. Dogs with maulstick legs and gibbet necks, salt-cod fried in brine and allspice, a can of Paddy’s Stout and Lager. Life is a game of chess without a chessboard, a plant without fascicles, a bountiful paucity, a sou'wester without a hatband or eyeshade, so he thought, to himself and no one else, the man in the hat thought.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

hATS aRE fOR pRINCIPLED pEOPLE*

In passing the man in the hat passed many people, many of whom wore hats, felt, wicker, corduroy and some stitched from flaps of canvas and oilcloth. He once saw a woman wearing a calfskin hat with a squirrel’s tail and a plastic bauble sewn into the crest. She, too, had a gamy leg which she dragged to one side like a weigh anchor. She also had a dog, a cross between a poodle and a foxhound, with tiny misshapen ears and a sharp pointed muzzle covered with wiry gray hair. She dragged it behind her like a dinghy, the dog sidling along the pavement, tiny legs like matchsticks, its ears cocked to one side, the leash garroting its neck like a gallows. Hats are for people with manners, he thought, not the unprincipled and shifty. He had a hankering to snatch the hat from atop her head, and then throw it into the gutter like a stray animal. But as he had better things to do, principled things that required manners and tenet, not shiftiness and connivance, he did not. His, the man in the hat’s, was a decent conscientious life, not one dross with bad manners and opprobrium.

Friday, August 25, 2006

tHE cLOCHARD'S hAT*

‘Is that yours?’ said the clochard, his eyes tightening under his hat. ‘Mine, of course,’ said the man in the hat, ‘my hat.’ The clochard rearranged the crease in his trousers, soiled through with Listerine and tobacco chuff, and smiled, a broad toothless smile. ‘This is mine’, he said, pointing at a bag of bread crusts at his feet, ‘mine, these here.’ The man in the hat cleared his throat and said, ‘yes, of course, yours not mine.’ ‘Bread crusts are like hats’, said the clochard. ‘Yes, I can see that,’ said the man in the hat. ‘Sometimes, said the clochard, his eyes tightening tighter, ‘I wear them, these’, he said, pointing at the bag at his feet, ‘like a hat, a bread hat,’ he said, smiling broadly. The man in the hat reasserted his hat, which he did when he felt amused, and said, ‘and teeth, bread crusts make wonderful teeth.’ ‘Yes, yes of course,’ said the clochard, his eyes retightening, the crease in his trousers loosening, ‘yes, teeth, of course.’ ‘Good bye,’ said the man in the hat, his hat reasserted, gamy leg stiffening from the cold. ‘So long,’ said the clochard, ‘and may God be with you.’

Monday, August 21, 2006

wINDBLOWN hATS*

Casserole dishes filled to toppling with carrots and beans, shepherd’s pie and Jell-O, day-old bread and watery fruit juices, a smorgasbord of castoffs and bitter ends. The man in the hat will eat to the soup, a consommé devoid of vegetables or legumes, but offer up his Jell-O to the chiliad seated across from him, his face a smear of hornet stings and bubonic spate. This is the way it is, the dimness of his life, the man in the hat’s life. If not for the soup, he would be nothing, a faint stand-in for nothing, a nothingness. When his leg tremors, which it does without fail, he, the man in the hat, rubs it with spearmint and balsam, a liniment that keeps the ache from reaching upwards and into the knell of his back, where it sits like a cataract clouding his vision, his ability to stave off the pain and discomfort. The soup helps to take his mind off the ache, discommode the feeling that something is not quite right, yet right just the same. Rightness has nothing to do with anything, yet he awaits the right moment, the moment when what is right will overtake what is right, yet was never right at all. The sky opens up like a malignancy, a supertanker bilge with dross and fish guts, his grandfather commandeering the Mercury Fish truck through alleyways, along side streets and up and over the sidewalk, pedestrians screeching like banshees, fingers clutching windblown hats.

Sunday, August 20, 2006

sEPTICEMIA*

The shamble leg man came across a beggar sitting cross-legged on the sidewalk, his almscap brim side up. ‘Those yours?’ he said, his eyesight straining, the beggar’s eyes septic with blood. ‘Those yours?’ he answered, pointing to a bag of bread-ends on the pavement beside him. ‘This is mine,’ said the shamble leg man, pointing at his great coat, ‘those, however, are yours’, he added pointing at the bag between the beggar’s legs. ‘So what is mine isn’t yours?’ asked the beggar. ‘Yes,’ said the shamble leg man, swiping a fly from the curse of his face. ‘Yes.’ ‘My bread is old, just odds and ends’, said the beggar, his eye weeping, ‘just ends and odds of bread.’ ‘But it’s yours’, said the shamble leg man, ‘not mine.’ ‘Yes, the bread is mine certainly, but the coat’, he said, pointing at the shamble leg man, ‘that is yours, not mine?’ ‘Yes,’ said the shamble leg man, that I am certain of.’ ‘I know of a man who likes soup, but abhors Jell-O,’ said the shamble leg man, the fly abuzz around his head. ‘If you can find him, which is improbable, as he tends to himself most of the time, he would gladly give you his Jell-O’. ‘But not the soup,’ said the beggar. ‘No, the soup he will not give up,’ said the shamble leg man, ‘that is his, and his alone’. ‘These are good things to know,’ said the beggar, ‘good things indeed.’ The shamble leg man turned to go, and said, ‘those are yours, yes?’ ‘Of course’, said the beggar, ‘mine, just odds and ends. Yours is a coat,’ he added, ‘and a fine one indeed.’ ‘Good bye,’ said the shamble leg man turning, ‘and indeed have a joyous day’. The beggar rearranged the bag of odds and ends between his legs, his eye septic with sleeplessness, and said, ‘and to you, too, sir, a good day.’

Friday, August 18, 2006

tHE tAIL oF hIS gREAT cOAT*

The shamble leg man trundled on two legs, one hidden beneath the tail of his great coat, and whistled high above himself, his lips pursed like sow’s ears. His skin, this morning’s skin, was oatmeal gray and blotched with sleeplessness; eyes trained on the pavement in front of him, hatless and locked in thoughtlessness. He seldom thought, and when he did, a thoughtless thinking with neither rhyme nor rationale. Whistling eased the pressure in his head, a pressure that had built up over years of poverty and aimlessness. His leg, the shamble leg, weighed heavily in his thoughts, the thought of a drag anchor that caused him to tilt and careen in circles, sometimes falling into a passerby or a lamppost, the tail of his great coat bluffing like a matted sail. Being said, he thought, is quite sad indeed.

Sunday, August 13, 2006

mR. sMITH

Mr

Smith

has

an

autistic

son

[and]

a metal

plate

in

his head

an

invisible

war

with voices

[and]

the television

Smith

has

an

autistic

son

[and]

a metal

plate

in

his head

an

invisible

war

with voices

[and]

the television

Saturday, August 12, 2006

eTHER rABBITS

I

watched

my

father

etherize

baby

rabbits

in a

shoebox

then

dig

a hole

under

the hedge

with

a shovel

watched

my

father

etherize

baby

rabbits

in a

shoebox

then

dig

a hole

under

the hedge

with

a shovel

hAT rEDUX

The shamble leg man awoke from a deep sleep; his eyes caulked with puss, and shook his leg free from the bed linen. He slept the sleep of the dead, the somnambulistic and dropsied. His palsy forced him to drink grain alcohols and spirits, cans of Listerine sprigged open at the bottom, the liquid culled into a plastic bottle, then mixed with Ginger Ale or Cola. He drank to stave off the trembling and quell the jimmying in his leg; tilting his head, he swigged back the churn in one forced gulp, an amniotic warmth gathering in his throat, spilling into the top of his stomach, then into the ulcers that ate away at the lining like rats.

A blue-gray morning sky, the world is trembling, a geomorphic shiver running down the line of my back, and as much as I try, I cannot fall back to sleep. Sleep will come when it’s ready, not a moment before. Some say that sleep is the thief of wakefulness; I say it is the penitence we pay for consciousness, the difference between alacrity and numbness, the reason for bed sheets and feathered pillows. The man in the hat thought things without reason or rhyme, a discordant faille, a cacophonous leitmotif, a monologue with two voices. He would, if he could, have no thoughts at all, and roughshod through life numb and unresponsive. He remembered hearing about how men with Van Dykes and pointy heads would drink themselves to perdition on absinthe distilled in wormwood casks, and that when opium was cooked too long, the alchemy produced a gummy slag that burned like sulfa.

A blue-gray morning sky, the world is trembling, a geomorphic shiver running down the line of my back, and as much as I try, I cannot fall back to sleep. Sleep will come when it’s ready, not a moment before. Some say that sleep is the thief of wakefulness; I say it is the penitence we pay for consciousness, the difference between alacrity and numbness, the reason for bed sheets and feathered pillows. The man in the hat thought things without reason or rhyme, a discordant faille, a cacophonous leitmotif, a monologue with two voices. He would, if he could, have no thoughts at all, and roughshod through life numb and unresponsive. He remembered hearing about how men with Van Dykes and pointy heads would drink themselves to perdition on absinthe distilled in wormwood casks, and that when opium was cooked too long, the alchemy produced a gummy slag that burned like sulfa.

mORPHINE and qUAALUDES7*

August Strindberg has a Van Dyke; I do not. Strindberg went horribly mad, insane with jealousy and alchemy; I have not, not yet. He wrote plays, books on necromancy and black magic, novels and diaries. I have a beard, trimmed close and neat to the scull of my face, and a hearing aide with a toggle switch to increase or decrease volume and humming. Strindberg wore well-tailored suits, serge and gabardine, pleated and double-breasted; I wear pony denim and rubber sandals with a silly insignia on the strapping. Strindberg had a fondness for the people of the islands of Stockholm’s archipelago; I was born on an island, one much smaller than an archipelago or a Stockholm. Strindberg’s grandfather was a spice merchant; mine a boiler-man from Liverpool. Strindberg is dead; I am not, not yet.

I raked the pump like a cat’s neck, sluing water from the tap head. My friends don’t like cats; nettle tongues and drivel hair and the clobber of sharp claws on hard linoleum. I found a litter familied beneath the silage shed, tongues raspy with spurs and awl pins. The others were fire setters, gas cans and sheet wicks twisted into funnels. Just the right size to tamp down hard into the throat of a castoff beer bottle or scout’s canteen. The doctor said that fire setting is a sign of childhood abuse, sexual improprieties carried out by addle-minded grownups and wet brains. The rector’s bench slatted with spindle elm and hard ash, the low susurrus of the calliope forcing chancel air through trued pipes, curds of stale bread and unction wine, draught from the parson’s own saintly tun. This is how it all began long before beginnings had names or reasons.

This is how I started, the beginning of what has become of me, the in between, what was left after the fall. As a boy my mother taught me to check my stool for inelegance and colour. A healthy stool was medium brown and shaped like a cone or foolscap. Anything darker or unshapely was deemed sickly, visceral canker. I had a friend who would poke about with a stick, roiling up his defecate checking for organs, dark blood and faille. His father, before succumbing to dementia, urinated in wine bottles he kept in a low drawer next to his bed. When he died we emptied the piss into the wash sink in the basement, my friend checking for bits of his father’s organs with the stick he used for his toilet. The piss smelled like death and spoiled wine. By the time his father was ready for death he had cornered himself into a box on the top floor of their house, cloistering himself like a penitent in a six by six beg cell. He had constructed his own coffin, furnishing it with empty wine bottles, a rosary and Popular Mechanics magazines. His death came as no surprise, a slow cancellation into madness and time. His wife’s Parkinson’s and flippered hands saved her from having to be sentry to her husband’s absurdity. Death is like that, a joke on the dying; an absurdity to those left behind to watch. My friend drank himself into a beg cell, piss bottles arranged in a votive altar to his father’s madness.

My father’s older brother drank himself into an early grave, leaving behind two ex-wives and as many children. He drove a yellow forklift, never quite mastering how to change to battery. My father’s oldest brother, who rode in the Jonah’s belly of a submarine in the Second World War, drank until his insides swelled up, his organs perishing like rotten fruit. At his funeral the older brother’s daughter climbed into his coffin and wept like a neglected child, tears brighten the cold meat of his face. Social Services put the youngest in a foster home, placing her cat with a family with a father and two small children. The oldest moved into a room downtown with a hotplate and a window overlooking the switching yards. We never visited them; the oldest found God in Morphine and Quaaludes, the younger in a foster father who taught her how to change her underpants and keep quiet. I never really knew either of my father’s brothers, but did learn how to change a forklift battery and row a boat. Death leaves behind memories, many not worth remembering or having.

I raked the pump like a cat’s neck, sluing water from the tap head. My friends don’t like cats; nettle tongues and drivel hair and the clobber of sharp claws on hard linoleum. I found a litter familied beneath the silage shed, tongues raspy with spurs and awl pins. The others were fire setters, gas cans and sheet wicks twisted into funnels. Just the right size to tamp down hard into the throat of a castoff beer bottle or scout’s canteen. The doctor said that fire setting is a sign of childhood abuse, sexual improprieties carried out by addle-minded grownups and wet brains. The rector’s bench slatted with spindle elm and hard ash, the low susurrus of the calliope forcing chancel air through trued pipes, curds of stale bread and unction wine, draught from the parson’s own saintly tun. This is how it all began long before beginnings had names or reasons.

This is how I started, the beginning of what has become of me, the in between, what was left after the fall. As a boy my mother taught me to check my stool for inelegance and colour. A healthy stool was medium brown and shaped like a cone or foolscap. Anything darker or unshapely was deemed sickly, visceral canker. I had a friend who would poke about with a stick, roiling up his defecate checking for organs, dark blood and faille. His father, before succumbing to dementia, urinated in wine bottles he kept in a low drawer next to his bed. When he died we emptied the piss into the wash sink in the basement, my friend checking for bits of his father’s organs with the stick he used for his toilet. The piss smelled like death and spoiled wine. By the time his father was ready for death he had cornered himself into a box on the top floor of their house, cloistering himself like a penitent in a six by six beg cell. He had constructed his own coffin, furnishing it with empty wine bottles, a rosary and Popular Mechanics magazines. His death came as no surprise, a slow cancellation into madness and time. His wife’s Parkinson’s and flippered hands saved her from having to be sentry to her husband’s absurdity. Death is like that, a joke on the dying; an absurdity to those left behind to watch. My friend drank himself into a beg cell, piss bottles arranged in a votive altar to his father’s madness.

My father’s older brother drank himself into an early grave, leaving behind two ex-wives and as many children. He drove a yellow forklift, never quite mastering how to change to battery. My father’s oldest brother, who rode in the Jonah’s belly of a submarine in the Second World War, drank until his insides swelled up, his organs perishing like rotten fruit. At his funeral the older brother’s daughter climbed into his coffin and wept like a neglected child, tears brighten the cold meat of his face. Social Services put the youngest in a foster home, placing her cat with a family with a father and two small children. The oldest moved into a room downtown with a hotplate and a window overlooking the switching yards. We never visited them; the oldest found God in Morphine and Quaaludes, the younger in a foster father who taught her how to change her underpants and keep quiet. I never really knew either of my father’s brothers, but did learn how to change a forklift battery and row a boat. Death leaves behind memories, many not worth remembering or having.

Friday, August 11, 2006

tHE sUMMER kITCHEN

And these nasty polemarks: [and] jammy tarts, the ones great aunt Alma made in the summer kitchen, crimping pastry into taffeta frills, [and] my great uncle Jim standing on the front porch, his good eye threaded with sweat, waving at tourist’s cars, [and] my dad eating date squares and rarebits of toast, {and} me sitting on the back stoop counting to one hundred backwards, making daisy chains with whistle grass and nettle fen, the afternoon fading into August night.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

kIDNEY sURD fONTANEL

A blue-quail morning, grey perhaps, oilseed, peroxide, mercurochrome scabbed over knees, brindle, puck black. I slept the sleep of the devilish, a bromide without a watershed, a crumpet without the butter-lard and pot-marmalade. Now I will pull a rarebit from the trumpet of my ass, a blaring, sonorous Dantean annunciation issuing from the scullery of my rectos. Gods’ morning to you all, rat’s asses and halyards cinched taut around Leopold and Blum. Molly’s skivvies hung out to dry, commode paper, Sears and Roan-buck, a kidney surd skillet-fried with onions and compote of barley. Daylight craving time, so much to get done, assonance, bad grammar and syntactical patricide.

Balzac’s hat had a hatband with quail’s foot scotched to the krimmer, right up side a fontanel that never quite hardened.

Corn syrup solids, hydrogenated soybean oil, sodium caseinate, dipotassium phosphate, sugar, artificial colour, mono and diglycerides, carrageenan, soy lecithin, artificial flavours, rats’ asses, zithers, monorail grease, machinist’s oil, e, gummy white crap, salver, parturition sweat, an old sweater with tattered cuffs, pre-seminal fluid, a snippet of cocks’ wattle, (yES) a cockscomb, brushed flat, (nO) protein, penicillin, uppers, downers or PCP.

I can’t write, even begin the process of writing, if I feel that I won’t have enough cigarettes to smoke non-stop, or almost non-stop. Any interruption in the smoking process is mercenary, robbing me of a healthy level of nicotine, a systemic toxin, dioxin, that I can’t seem to live without, though I suppose I should, given the pulmonary/respiratory thievery that tar, benzenes, lipids and all such venomous inhalations incur in an otherwise hale and hearty body. I smoke as a means of regulating my Grammatik misuse of syntax, tropisms and proper spelling, none of which I seem hale and hearty at. Wait, please, as I light another cigarette, the last one I will smoke while writing this exercise in trivial banality. Fuck it; I’m going to bed, coughing myself to sleep like a hogshead with ineluctable emphysema

I have a dream, he said, an ineffable, marvellous dream. Molly sidles up close to me, her breath sour with whey and Paddy’s, bloomers cinched round her neck, a cock’s wattle. She leans in close, the cinnamon sweet treacle of her hair cussing the bevel of my cheeks, and whispers, Yes I will, yes, Yes…I said Yes. I collapse, implode in on myself, a rasher of kidney and allspice, a page of Sears and Roebuck’s clutched between fore and thumb, her whisper like diamonds in my hand.

I live in a coalhouse, a livery of thoughts. Like a Derridian corm I have neither a beginning nor and end, but simply a jumping-in point, a coaxial imputation, a frogfish leap. Language is thought is unreason, hepatisation, derision, a trebuchet without a weighbar. Drink Coca Cola, you rotten bastards. No transfats or lipids, no smarmy lard or yellow blubber. My entire life, my sensate-me, is a pixilation, whatever the screen permits, the mind consents to, makes blubbery and sincere, impetrates and collates, scullery-whores with wee tiny teeth and amulet smiles: minutia.

I am a montage, a collocation of this and that, that and this, a rhizome without an exit hole, a Heideggerian leap, I am oedipalization and Grammatik patricide; MOMMY DADDY chider (ren), blather, blither mater; a staccato censoriousness with flutes and oboes, Frenchman’s horn and tubing. I am neither either or, nor am I either neither or. I am a Derridian gramophone, Joyce’s patchy-eye, Beckett’s dustbin, a sandbox full to brimming with scats, a savant with a mind for figures, and calculus and logarithms, and vectors that go onto and out; a slide Muller, a cuckolder without a cuck. I am a demy-colon, a comma-lot, and a Shakespearean Moor shoeblack with envy and bad manners. I am all of these, yet none; I am a montage, a collage of this and that, that and this, a cuckoldry of word and text, a poet with a fancy for dissonance and bad manners.

Should you care to listen, I will tell you about the grisliness of alcoholism, the Dantean declension into hell. I have been there, crawling like a child on scabby knees, without a Virgil or a poet to show me the way back up, out of the horror of Dis’s hell. I climbed on the back of a behemoth, a monster, an obsession to repeat, to become again that which I feared and reviled, the colossus within, the ogre whose thirst is never slaked. I am here to tell you the story, the story of my ascension into hell, my fistfight with the beast, the colossus that seeks revenge for temperance and prohibition.

Some days, the days in between, those enigmatic messages handed down from mommy-daddy, an unconscious caterwaul, a dissonant dissonance. When the mettle becomes meddlesome, the knifemen make the incision just below the pineal gland, at the base of the ganglia, rending free the hypothalamic sac, the harbinger of toilet training and object relations; a depersonalization, a sterility of thought, cantor and mien. Good breast bad breast, a signified without a signifier, a detached psychical retina, a finger-painting with feces and lye, a child’s wane cry, sycophantic and cowering under the balustrade of daddy. The tower of Babel started it all; the signified without a signifier, the enigmatic messaging, mommy-daddy, child, the oedipal strangulation, seeking forgiveness for sins never committed, a logician’s slight of hand, Dedalus’ wings weight down with slander and canonical tallow.

Who’s running the asylum? The deconstruction of the psyche, the loss of the individual, the panoptical reification of the idiosyncratic, the Other other, the otherness of the Other other, turned in on itself, the gaze gazed upon the gazer, the self-borstal-self. No psyche, no internal machine, a desiring machine, a coveting machine, but a socialized communal other, with neither self nor otherness, the other reified and jailed within the public sphere, the numinous gaol. Detained within the self, one eye trained on the other, the other trained on the otherness of the other, the public self: madness, loss of self, corruption of self-psyche-self, a panoptical no-man’s-land, psychopharmythology, chemical Bedlam, a Foucaultian nightmare.

Balzac’s hat had a hatband with quail’s foot scotched to the krimmer, right up side a fontanel that never quite hardened.

Corn syrup solids, hydrogenated soybean oil, sodium caseinate, dipotassium phosphate, sugar, artificial colour, mono and diglycerides, carrageenan, soy lecithin, artificial flavours, rats’ asses, zithers, monorail grease, machinist’s oil, e, gummy white crap, salver, parturition sweat, an old sweater with tattered cuffs, pre-seminal fluid, a snippet of cocks’ wattle, (yES) a cockscomb, brushed flat, (nO) protein, penicillin, uppers, downers or PCP.

I can’t write, even begin the process of writing, if I feel that I won’t have enough cigarettes to smoke non-stop, or almost non-stop. Any interruption in the smoking process is mercenary, robbing me of a healthy level of nicotine, a systemic toxin, dioxin, that I can’t seem to live without, though I suppose I should, given the pulmonary/respiratory thievery that tar, benzenes, lipids and all such venomous inhalations incur in an otherwise hale and hearty body. I smoke as a means of regulating my Grammatik misuse of syntax, tropisms and proper spelling, none of which I seem hale and hearty at. Wait, please, as I light another cigarette, the last one I will smoke while writing this exercise in trivial banality. Fuck it; I’m going to bed, coughing myself to sleep like a hogshead with ineluctable emphysema

I have a dream, he said, an ineffable, marvellous dream. Molly sidles up close to me, her breath sour with whey and Paddy’s, bloomers cinched round her neck, a cock’s wattle. She leans in close, the cinnamon sweet treacle of her hair cussing the bevel of my cheeks, and whispers, Yes I will, yes, Yes…I said Yes. I collapse, implode in on myself, a rasher of kidney and allspice, a page of Sears and Roebuck’s clutched between fore and thumb, her whisper like diamonds in my hand.

I live in a coalhouse, a livery of thoughts. Like a Derridian corm I have neither a beginning nor and end, but simply a jumping-in point, a coaxial imputation, a frogfish leap. Language is thought is unreason, hepatisation, derision, a trebuchet without a weighbar. Drink Coca Cola, you rotten bastards. No transfats or lipids, no smarmy lard or yellow blubber. My entire life, my sensate-me, is a pixilation, whatever the screen permits, the mind consents to, makes blubbery and sincere, impetrates and collates, scullery-whores with wee tiny teeth and amulet smiles: minutia.

I am a montage, a collocation of this and that, that and this, a rhizome without an exit hole, a Heideggerian leap, I am oedipalization and Grammatik patricide; MOMMY DADDY chider (ren), blather, blither mater; a staccato censoriousness with flutes and oboes, Frenchman’s horn and tubing. I am neither either or, nor am I either neither or. I am a Derridian gramophone, Joyce’s patchy-eye, Beckett’s dustbin, a sandbox full to brimming with scats, a savant with a mind for figures, and calculus and logarithms, and vectors that go onto and out; a slide Muller, a cuckolder without a cuck. I am a demy-colon, a comma-lot, and a Shakespearean Moor shoeblack with envy and bad manners. I am all of these, yet none; I am a montage, a collage of this and that, that and this, a cuckoldry of word and text, a poet with a fancy for dissonance and bad manners.

Should you care to listen, I will tell you about the grisliness of alcoholism, the Dantean declension into hell. I have been there, crawling like a child on scabby knees, without a Virgil or a poet to show me the way back up, out of the horror of Dis’s hell. I climbed on the back of a behemoth, a monster, an obsession to repeat, to become again that which I feared and reviled, the colossus within, the ogre whose thirst is never slaked. I am here to tell you the story, the story of my ascension into hell, my fistfight with the beast, the colossus that seeks revenge for temperance and prohibition.

Some days, the days in between, those enigmatic messages handed down from mommy-daddy, an unconscious caterwaul, a dissonant dissonance. When the mettle becomes meddlesome, the knifemen make the incision just below the pineal gland, at the base of the ganglia, rending free the hypothalamic sac, the harbinger of toilet training and object relations; a depersonalization, a sterility of thought, cantor and mien. Good breast bad breast, a signified without a signifier, a detached psychical retina, a finger-painting with feces and lye, a child’s wane cry, sycophantic and cowering under the balustrade of daddy. The tower of Babel started it all; the signified without a signifier, the enigmatic messaging, mommy-daddy, child, the oedipal strangulation, seeking forgiveness for sins never committed, a logician’s slight of hand, Dedalus’ wings weight down with slander and canonical tallow.

Who’s running the asylum? The deconstruction of the psyche, the loss of the individual, the panoptical reification of the idiosyncratic, the Other other, the otherness of the Other other, turned in on itself, the gaze gazed upon the gazer, the self-borstal-self. No psyche, no internal machine, a desiring machine, a coveting machine, but a socialized communal other, with neither self nor otherness, the other reified and jailed within the public sphere, the numinous gaol. Detained within the self, one eye trained on the other, the other trained on the otherness of the other, the public self: madness, loss of self, corruption of self-psyche-self, a panoptical no-man’s-land, psychopharmythology, chemical Bedlam, a Foucaultian nightmare.

wHERE’s mY pENCIL?

I fell upon it, he said, stumbling in the dark, stocking feet catching a loose nail in the carpet tacking. It was there, just there, a thing without a name or a purpose; no this or that, a thing of nothing, a non-thing, thing. It was there, I swear to you it was, just as I saw it, just as it was in my mind’s eye. It was there, there over here, there, to the left of here but not there, the right of there but not here; over there, somewhere there, not here, there, for the love of it: there. You do believe me, don’t you, it was there, really it was, over there, not here, there, away from here over there, there, really it was, just as I saw it. If you don’t believe me, so what; it doesn’t matter, makes no difference to me, none. I saw it and that’s all that matters, there, where I saw it, a loose nail in the carpet, sticking out of the tacking, there, over there, no, not there, there. If I see it again, no matter where, either there or here, here or there, the thing without a name, without a purpose, I will tell you about it, again, I will tell you again, about it, the thing that is no thing, the non-thing, the thing that was there, but is no longer there. I fell upon it, after all, in the dark, in my stocking feet, my feet (I point down, there), my feet, these, there, my feet there, stumbling in the dark, without a name or a purpose, just a there.

I ate, no goblet(ed) a bologna sandwich this evening on primpknuckle and lye, a soft whereabouts in the labium of me mouther. She, she did, tied a lariat round the wattle of my neck(tyke), cinching it tight with a Scout’s knot, fleche(ing) the knead to butter me wrongsideup, like a sideplate of melbas, cracked wheat and wry. Fucking cough medicine’s going to be the end(son) of me. Beckett’s crockpipe finger between thumb and fore, no endgame for Ham or Plink or some ruffian in a tackman’s hat; now tell me please, if you might, whereabouts the clubmaster with the frottage cheese and cowslip lip, the one with the baby tuk tuk and Dedalus smile, and wee Aquinas first principle, be that Muslix or Cripper, or a vicar’s surplice fleeced with hopscotch, applejack, or a Eucharist Jell-O in a firkin’s jampot wrongsideup.

I prefer, he said, a sideplate of toast smeared with oleo of lard, perhaps, he said, a curd of allspice with a Burgee’s nM4*, or a pumpernickel, black as the ace of spondees: Or, for that mutter, a skim of tappet simmered with oil of egress and oxblood soupcon [he said] the kind that sullies the palate and vectors the wee Tilley. I ambulate, he said, with polio boot and ashplant striking the pavewalk like a firewood match, sulfur yellow and quidbrown like Blazes gobspit, Mully’s thingwort slathered with allornothing. No: he said: a marmalade compote, or a measure of jamjelly scone(d) on the farplate next to the cinderbox powdery with oldperson’smints and the odd biscuit, chewed from the insod out. Mansebevel hidden in the rector’s closet, where a knockabout of wee Tully’s eat macadam bread patted with aster of Goethe, Writher’s head shorn clear off his shoulderigging: Or, [he said] a barilla of tin biscuits, the sort that me great aunt Alma made with recto cloth cinched round the coop of her reddress, the (verily) one she wore on Somedays and those that fell between heathen and haycock. Barging that, he sod, a wedge of the bluecheese, the allsorts that grandmamma pressed in briecloth, the wee buggers playing the loop-de-loop in the barrows of her skirts. [He said] nary muck of impute [he said, saying], I prefer a Burgee’s nM4*, or a cold August night boiled in a samepot with boxthorn and pumperknuckle, a sideplate of skimming and quillworst.

Murphy fownd a horsis hede in the bruwn rivar that ran across tha beck of thair properte whair a juneiparberre hedge clung ta lif amidst tha rock an dirt an a stend uv poplars cutcrucked an ran paralell ta tha rivar. Tha frunthede wuz crushd in at tha temoral lobe an a tangle uv seeweed crept out frum between a fizzure in tha gray skullbone that met up with tha eyesockets. Thair wair a nest uv eels crevassed in tha nostrilholes an a green gelatinus lump in tha vallt uv tha mowth. Whair tha teeth met with tha jaw a whileenamel bonespur connectd with tha hinge undar tha ear pessages whair anuthar eel had fownd a purchase. Murphy had heerd that fisharmen oftin used horsis hedes to cetch eels in tha wetar sirounding tha opinfeelds. He had alsew seen a man with a longthin nife cut throo tha muscle an tenduns uv a horsis leg an hobbled it on tha spot. Tha horse wuz than broken ta tha grownd an lay thair in a puddal uv its own blood. He had heerd that tha horse wuz too old ta do ane farmwerk an wuz put down as a conseqwence uv that; an that wen a horse wuz put down, tha fermar alweys cut its hede off an sold it ta a fisharman that livd in a cettage neer tha brownrivar. I thinc I mite be otistick; I inhabit two divergant realitees that cennot cum inta contect with oneanuthar. If thay did, tha results wood be catastrofic.

Proust smoked corkboard cigarettes rolled between thumb and forefinger, lips scabby with anise and fontanel. He wrote books. He scribbled madly cloistered away in his flat; the windows grouted with rags, legs crossed and latticed, knees bent into a Gordian knot, culottes tucked into the fob of his trousers. He is dead, a virulent reaction to kerosene and short pants.

Rarebit toast lye with Thomas’ liver, skillet-fried with onions and coarse garlic. Charon poling the Liffey, lips smacking, Dante’s lingerie swaying from halyard and dowelling. Oedipus shed not one tear, mother-coitus, saddle sore and humping like Diogenes on PCP. I will give you all my unkingly things, should you move just a hair to the left, as you’re blocking the sun from balming my face, you empyrean scoundrel, king of Moyle’s and Schwartz, thug and rampart, chewer of prepuces and Wriggle’s.

Pencil prehensile, Damsel washerwoman, scullerywhore, impetigo, Tobago, that fucking Winnebago you bought for a song, dirge(y) bastard, scant knowledge of vectors and algebra, logarithms are the devil’s work, Samuel Johnson ate mutton jerky, sicker than Hemmingway’s cow(lick), my proctor, doctor greatcoat soiled with Cooper’s oil and jampot jemmies, silly fuck with a tonsure cut round river runs past and on, patchy cunt with a satang bunnyclip(ity) clop goes the rector’s closet full to brimming with wafers and jamjuice made from plums and civet seeds cowl(ed) from the boot of me daddy’s Buick with the fiveanddime beebonnet on the fader’s mirror image of Mr. T. Mann’s postseminal chappings, sad mixed up Buddenbrooks with the blackest pair a lungs you(will) ever see.

I have a headcheese head, compote of viscera and tripe, an inelegant skullcap replete with tassels and flange: hard Etruscan bone, Tamil perhaps, a bulwark from the scourge of scourges, dispatches, junk-mail, the edicts of a demiurge with misshapen feet and an alphorn simper. I eat what is inedible, malarkey, cesspit chowder, an oleo of other’s castaways and rot. My great uncle Jim refused to eat anything green, vegetables, mint teas, anything gangrenous and wholesome; kales, peas, beans, navy, bunion, chick or Lima. He had one eye, two hands and a shamble foot, a leghorn that he dragged behind him like a wan calf, tongue lolling, dead from heat exhaustion and frenzied saltlick clobber. Screen memories are like that, unsubtle and rife with mercurochrome and brine.

I am the eggman, I eat haggis and roiled oats, and a muddle of foodstuffs that defy gastro-oesophageal description, and if they did, would make you sick and incontinent with bedsores. I am the jam custard that leaks from the labia of your sandwich, a Hoagie rich in iron and samesuch, a rutabaga yanked begrudgingly from the dirt, a child’s chocolate smile, dimples clove with allsorts and wheat germ. I am liquorice root and weasel ole, panoply of fennel branch and Lime Ricky left out too long in the sun, spoiled and clenched round the edges. I am a pat of white butter, a scupper of en-margarine-ated soy oil, the benchmark of a hale and heady diet, a rooster’s cockscomb combed to one side, a clop of brills’ cream moistening the cowlick on the miser of my head, where flea bodies and lice scrabble for not so dear life, their’s a life of entomological chicanery and Manhattan’s without a cherry or frig of lemon. I am all of these but none of these, I am panoply of this and that, that and this, a trope without a tropism, a hat without a hatband, a felt tipped pen quill that scribbles Joe nu says quoi. Good night, and may clods bless.

Again I awake to the mice scurrying in my head, having, as I do, the thoughts of a carbine, a repeater, a twelve-shooter without a silencer. This is mercenary, this fucking Turing Machine, this brainpan scurvy with Gomorrah and Brine-Peter. The Diagnostic manual, Emmanuel, refers to it, this repeating repetition, as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, more aptly referred to as Obsessive Repulsive disarray: this flowchart with nary a plus or minus, an into or out of, no subtractions or divisions, just one uninterrupted algebraic scribbler, the orange one with the crinkles and inkpot blain on the cover. It took me two years of minus and pluses, into’s and out of’s, to master the basics of mathematical certainty, calculus’, rhomboids, vectors and divisiveness’. Quaaludes and crystal myth, arithmetic savantism, a vagrant’s alms cap, brim side down, collecting numbers, and the fucking mice, scurrying like banshees in the Skinnerian Box of my head.

I ate, no goblet(ed) a bologna sandwich this evening on primpknuckle and lye, a soft whereabouts in the labium of me mouther. She, she did, tied a lariat round the wattle of my neck(tyke), cinching it tight with a Scout’s knot, fleche(ing) the knead to butter me wrongsideup, like a sideplate of melbas, cracked wheat and wry. Fucking cough medicine’s going to be the end(son) of me. Beckett’s crockpipe finger between thumb and fore, no endgame for Ham or Plink or some ruffian in a tackman’s hat; now tell me please, if you might, whereabouts the clubmaster with the frottage cheese and cowslip lip, the one with the baby tuk tuk and Dedalus smile, and wee Aquinas first principle, be that Muslix or Cripper, or a vicar’s surplice fleeced with hopscotch, applejack, or a Eucharist Jell-O in a firkin’s jampot wrongsideup.

I prefer, he said, a sideplate of toast smeared with oleo of lard, perhaps, he said, a curd of allspice with a Burgee’s nM4*, or a pumpernickel, black as the ace of spondees: Or, for that mutter, a skim of tappet simmered with oil of egress and oxblood soupcon [he said] the kind that sullies the palate and vectors the wee Tilley. I ambulate, he said, with polio boot and ashplant striking the pavewalk like a firewood match, sulfur yellow and quidbrown like Blazes gobspit, Mully’s thingwort slathered with allornothing. No: he said: a marmalade compote, or a measure of jamjelly scone(d) on the farplate next to the cinderbox powdery with oldperson’smints and the odd biscuit, chewed from the insod out. Mansebevel hidden in the rector’s closet, where a knockabout of wee Tully’s eat macadam bread patted with aster of Goethe, Writher’s head shorn clear off his shoulderigging: Or, [he said] a barilla of tin biscuits, the sort that me great aunt Alma made with recto cloth cinched round the coop of her reddress, the (verily) one she wore on Somedays and those that fell between heathen and haycock. Barging that, he sod, a wedge of the bluecheese, the allsorts that grandmamma pressed in briecloth, the wee buggers playing the loop-de-loop in the barrows of her skirts. [He said] nary muck of impute [he said, saying], I prefer a Burgee’s nM4*, or a cold August night boiled in a samepot with boxthorn and pumperknuckle, a sideplate of skimming and quillworst.