Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Thursday, June 22, 2006

bURGEE's mEDICINAL tONIC7*

She, the shamble leg man’s mother, died from impetigo and a virulent strain of whooping cough. She died corrupted; her lungs prowl with spirochetes and blackness. After her funeral mass, he read up on thalidomide and spirochetes, and virulent strains of whooping cough that blackened lungs like roofer’s tar. His shamble leg was his penance for not having grieved for his mother, for burlap skirts, vinegary breath, whooping, and the uneasiness in the crucible of her stomach.

One day among many, the man in the hat was out for a walk when he came across a beggar sitting with his hands crossed over his chest. When he asked, ‘why are your hands crossed over your chest like that?’ the beggar replied, ‘so my heart doesn’t jump out and run away’. ‘Oh’, said the man in the hat, ‘I see, you’ve got a fast heart is it?’ ‘No’, said the beggar, ‘I’ve got diabetes and my legs are all shaky and full of holes.’ The man in the hat tipped the brim of his hat and said, ‘better than a hole in the head, I suppose.’ ‘Any day’, replied the beggar, ‘shaky legs, too.’ A gun metal blue-gray sky and the man in the hat without an umbrella or cover for his hat; if it were to rain, which it might, he’d be left drenched and sopping. He looked down at the beggar, who was busy rearranging and sorting through his alms-cap, and smiled. ‘Might you have a spare plastic bag for my head?’ The beggar looked up, eyes straining to see the man in the hat, as the sun was broiling, and said, ‘why of course, yes, yes I do.’ He fiddled and scrounged through his belongings, a rucksack with string tied round the zipper eyelet, an old potato fermenting in a plastic bag, and his alms-cap, red and black with the coat of arms of the Vatican on the brim tip. ‘Here,’ he said, offering a grocery bag to the man in the hat. The man in the hat took the bag from the beggar’s hand and smiled, ‘so kind of you, so kind indeed.’ ‘You need some string for that?’ the beggar said, his eyes like moths. ‘Might be a good idea,’ said the man in the hat, ‘a good idea indeed.’ ‘You can use it to tie it round your chin, that ways it won’t blow off.’ ‘Right,’ said the man in the hat, ‘right you are.’

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

pEROXIDE and cLOVE oIL7*

The shamble leg man was known to drink thermoses of Whisky and dry Vermouth, cupfuls of broth sluiced with Listerine and Burgees’ medicinal tonic. He gargled with peroxide and clove oil, a recipe handed down from his grandmother, a seamstress with gray hair and a lazy eye that twitched like a metronome. She boiled burlap sacs in yeast and vinegar, and then stitched the sacs together with fishing line and a bone needle she kept in a mahogany box on her dresser. She called them chattel dresses, not burlap taffetas or sac cloth gussy ups. His mother, the man with the shamble leg’s mother, wore sac-cloth and burlap, scullery dresses roily with yeast and vinegar, chattel skirts with uneven hems and stitching. She smoked non-filtered cigarettes, Export A’s and Player’s, and drank Burgee’s medicinal tonic to stave off the chills and quell her jimmy-legs. She ate watercress sandwiches smothered in mayonnaise, and Rye Melbas that pricked her gums, beans with gravy and celery root, and anything boiled in a pot, hocks and shoulder, butt and cow’s tripe salted with brine. She loathed her mother, and took every opportunity to hide her bone needle, the one she kept in a mahogany box on the dresser. She took thalidomide for the queasiness in her stomach, and spat out her son, the shamble leg man, like a rotten oyster.

Sunday, June 18, 2006

mEAT-eNDS ans gRISTLE7*

The man in the hats great aunt Alma turned her own blind eye to her husband’s peculiarities, his cursed over anxiousness for green things and kale. The heat in the soup kitchen was inhospitable, an infestation of flies and scalp lice snapping against trouser hems, loading up on scatter and waste, mandibles truant with beans and gravy. ‘You want them dumplings?’ ‘Fuck off, I’m trying to eat’. A churl of pork bone loosening a tooth, spit up onto a plate lousy with meat-ends and gristle. ‘You want them meat-ends?’ ‘Can’t you see I’m trying to eat, leave me the fuck alone?’ ‘The soup, what about the soup?’ ‘Fuck off!’ Aunt Alma’s kitchen sugary with cinnamon and nutmeg, raspberry tarts left to cool on the window ledge, Uncle Jim shuffling his feet beneath the tabletop, truant with anxiety and small-mindedness. My great Uncle sheltered himself from green things, and slurped his soup like a madman, one eye on the windowsill, the other milky with spoil, made by a glassblower with a clove-lip and a black moustache he twirled at the ends.

Saturday, June 17, 2006

2@hAt7*

A molt gray sky is better than no sky at all, reflected the man in the hat. Thinking has its drawbacks, as do skies, blueness, and a green greenness that inveigles and atropines the eye, a pustule of socket and cornea. His plant, the one plant he owned, wept for hydration, moist waterwheel soil, not hard Bedouin till. He fed it spittle, excreta, a watershed of backwash, or simply left it to wither, like a placenta left out to dry on a scrub board, cordless and feeble. Like his great uncle, the man in the hat had no liking for green things, beans, string or whole, peas, armored or shucked, Lima, split or dismembered, broccolis or asparagus. He hid green things beneath the clatter of his plate; his nose turned up like a spoiled child’s, knees thumping the bottom of the table like a distressed kite. His good eye flittered like a tiger moth, crepe with custard and sleep. He lost the other one, the bad eye, in a sawmill accident, flint wood piercing the cornea clear through to bone.

Thursday, June 15, 2006

tHOMAS' lIVER

Some people are fated with Thomas’ liver, sopped with Port and Paddy’s cure-all, a phonetic mess of dilettantism and Welsh bolshie’s, a portrait of the drunkard as a young dog: her liver the size of a soccer ball, bloated and septic with corpsegas, briny with carrion and lye. She drinks to assuage the tremors, the scourge of Saint John’s Wart: hogshead tripe with blood pudding, an earwig salad, a light vinaigrette on the side plate, not for the faint of stomach or kidney, renal failure and so-and-so. Her children sat in the squalor of her thoughts, reading takeout menus and other people’s mail. Linking sausage to sausage, Eaton’s sells blood pudding casing, twenty-five to the dollar, skillet-fried with bacon rind and allspice, a peppering of confectionary sugar to stave off the spoiling aftertaste in the scrotum of her throat, a banshee screeching in the pendulum of her sternum. The man in the hat felt neither pity nor sadness for the woman, as he had more important things to attend to, three-legged dogs and wingless birds, shelter soup and scum topped Jell-O. Perhaps, he thought, I will offer my soup to the shamble legged man should next we meet, and save the Jell-O for a late night treat, or save it for the girl with the hearing box haltered to her chest, as she deserves more pity than scorn.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

2@9*hAT

Nights are cold, thought the man in the hat, cold with worry and fretting. Wrapped like a sausage in tripe, the man in the hat slept the sleep of the sleepless and troubled. An embolism, he thought, perhaps I have an aneurysm waiting to implode in the tomb of my head, blood pudding, a foul tureen or consommé. Too much dog meat, he thought, sinewy and undercooked. The pressure was assuming a life of its own, pushing in on the walls of his skullcap, inching its way into the viscera of his mentality. Soon, so he thought, his thoughts would be a scrabble of misnomers and tropisms, improper spelling and grammar, a catalogue of misjudgments and folly. His hat, yes my hat, that is all that’s preventing me from falling in on myself, collapsing into myself, my innerness, he thought. A tropism of hats, some with tassels and baubles, and others with felt liners and calfskin outers. He recalled, against his better judgment, a woman he knew whose father forced her to eat blood pudding and headcheese for breakfast, a placental mush stirred bloodied with a fork, wingtips of blood and gruel discolouring her face, a clownish smile gone terribly wrong

Monday, June 12, 2006

tHE hABERDASHER7*

A soup bone gray day, a saltlick of clouds above his head, the man in the hat’s thoughts on veal chops and chicken legs, figs and a thermos of black tea minted with anise and allspice. The haberdasher that tailored suits for the man in the hat was neither Italian nor Portuguese, but rather Angolan, but of a pale brown complexion. He wore a fez, red with blue and yellow tassels, and seldom spoke unless spoken to. He made extraordinary suits, serge and gabardine, wide-lapelled and narrow, double-breasted and single, fob pocketed or sporty. He smoked kef, though sparingly, and ate little other than chick peas and parboiled rice, generally wild, brown and glutinous. His wife had one eye, the missing one gouged out by a less than propitious ex-lover who worked as a sommelier for a small West African restaurant. She smoked long slender cigarettes, which she held between her thumb and forefinger, but found kef unsavory and odiferous. She didn’t mind that her husband partook of kef, but rather he smoked it in the storeroom or the alleyway behind the store. The haberdasher tailored suits from hemp, smoothing out the seams and folds with a steam iron that hung from the ceiling with box twine. He generally smoked kef in the evenings, once the day’s work had been done, and his wife had gone out to play bridge or pinochle, which she did most nights, thereby avoiding the numinous pong of kef. ‘May I ask what side you dress on?’ asked the haberdasher. ‘Either side, it doesn’t much matter’, answered the man in the hat, his hat off centre to one side. ‘Might I suggest?’ added the haberdasher, ‘that to the left is most suited to a man of your stature, as it will allow for a freedom of stride I believe you will find most satisfactory’. ‘Thank you.’ Said the man in the hat, ‘of course, as you suggest, after all, it is you that tailor the suits, not I.’ ‘As you wish, dear sir.’ The haberdasher reached for his chalk and sighed, ‘what a day indeed,’ he said, ‘my dear wife has a dislike for kef, which, as you know I smoke, though sparingly of course’. The man in the hat shifted his weight form one foot to the other, re-cocked his hat, and closed his eyes. ‘Of course, please feel free to light one up; it certainly makes no difference to me.’ The haberdasher drew a curved line along the inseam of the man in the hat’s leg and smiled, full toothsomely. ‘You are too kind’, he said, ‘and, might I add, a fine gentleman, both courteous and unduly considerate.’ ‘If you like,’ said the man in the hat, ‘I have some Jell-O you might find of interest, strawberry and kiwi’. The haberdasher drew one last chalk line on the man in the hat’s trousers and said, ‘yes, so kind and considerate indeed.’

Saturday, June 10, 2006

sKY pIMPS

The sun is hiding, he thought, holed up in the barrows of a whore’s skirts. The clouds are the sky’s pimps, feathered hats, pigskin eyes, hogsheads. The rain and brusque wind oblige the shamble legged man to skim across the top of the pavement like mercury. He moves like graffiti, curlicues and haloes of colour. There is nothing more inveigling, thought the man in the hat, than the truth. The truth being what one is accustom to accepting as true, an act of inveiglement, a pimply way of getting what one wants. Hogshead soups, brothel gumbo, bouillabaisse, molder and commode, a purulent fester of rancid mutton ladled into outstretched bowls.

Thursday, June 08, 2006

mAN28*

The man in the hat looked at the man with the shamble leg and frowned, ‘never the soup’. The man with the shamble leg sighed, his lips tightening like sail thread, and said, ‘Jell-O’s better than soup anyways, soups too hot, anyways’. He swung his left leg over his right leg and pushed his plate across the tabletop, his eyes two specks of watery garnet. ‘Fritters’, said the man with the shamble leg, ‘corn fritters.’ ‘Pocked,’ said the man in the hat. ‘Yes’, replied the shamble legged man, mocked with corn’. ‘Pocked,’ added the hat man, ‘not mocked’. ‘Pocked with mocked corn’, said the shamble legged man, ‘pock mocked with yellow corn, yes, corn’, he said, ‘yellow mocked pocked corn, fritters, corn fritters’. “I see’, said the hat man, ‘yes, I see. Pock mocked with corn, fritters of mocked pocked corn.’ ‘Fritters, yes,’ said the legged man. ‘I hear you,’ said the man in the hat, ‘loud and clear.’ ‘As a bell’, added the shambled man. ‘Pealing and pinging and chiming’, said the man in the hat man. ‘You want your soup?’ asked the shamble leg man. ‘Jell-O,’ replied the man in the hat, ‘not the soup, never the soup.’ ‘Like a bell,’ said the shamble leg man, ‘like a chiming, pealing pinging bell.’ ‘You are welcome to the fritters,’ said the man in the hat. ‘Pocked with mock corn,’ added the shamble leg man. ‘Mocked with pocked corn, yes,’ said the man in the hat. ‘Corn fritters, yes, never the soup,’ said the shamble leg man. The shamble leg man swung his right leg over is left leg and sighed, ‘always the Jell-O, never the soup’.

The sun is hiding, he thought, holed up in the barrows of a whore’s skirts. The clouds are the sky’s pimps, feathered hats, pigskin eyes, hogsheads.

The sun is hiding, he thought, holed up in the barrows of a whore’s skirts. The clouds are the sky’s pimps, feathered hats, pigskin eyes, hogsheads.

Wednesday, June 07, 2006

dEMENTIA sOU'wESTER

He was a truant thinker, thinking thoughts not based in accepted wisdom, incomplete, inarticulate thoughts. He thought thoughts at random; series and computations of thoughts thought backwards and forwards, forwards and backwards, an incoherent garble of pretense and dimwittedness. When not wolfing down birdseed and apple skins, he sat at the table across for the man in the hat, his sou'wester folded crosswise on his lap, eyes blank as death. He was loosing his mind to dementia praecox. He heard voices, yowling tenors, high-pitched sopranos, deep guttural bassos. He saw spiders and millipedes, toads and sprites, dead raccoons and earwigs. He sat, the man with the shamble leg, in the absence of his thoughts, thinking backwards, then forwards, then neither forward or back. He sat sitting, dreaming of birdseed and apple skins, loosing what little mind he had left to voices and pictures that roamed the scourge of his brain, squelchy with Listerine and breath mints. Nothing happens for a reason, thought the man in the hat. Not even nothing, he thought, not even that. Everything is accidental, haphazard, unsystematic, and not worth the bother of bothering about. More ink than words in the Bible, he thought, how bad mannered, obscene, but not worth the bother still. Loosing one’s mind seemed a small pittance to pay for an acquittal from the madness, the obscenity of it all.

‘You want your soup?’ the man with the shamble leg asked the man in the hat. ‘Jell-O’, he replied. ‘You are welcome to the Jell-O, but not the soup’. The man in the hat shuffled his feet beneath the table, ‘Jell-O, strawberry with fruit bits in it, your welcome to that. Not the soup?’ said the man with the shamble leg. ‘Not the soup, never the soup’.

‘You want your soup?’ the man with the shamble leg asked the man in the hat. ‘Jell-O’, he replied. ‘You are welcome to the Jell-O, but not the soup’. The man in the hat shuffled his feet beneath the table, ‘Jell-O, strawberry with fruit bits in it, your welcome to that. Not the soup?’ said the man with the shamble leg. ‘Not the soup, never the soup’.

Monday, June 05, 2006

mAN2*7

Another man with a pear-shaped head, hair matted in cornrows, spun a tale of abuse and maltreatment at the hands of the police, a litany of beatings and sharp invectives. Paranoiac gibberish, a cacophony of inarticulate voices, word salad, echolalia, he spoke in riddles and hexes, like a Skinnerian child in a wooden box, a Bedlam outpatient. Men with boxthorn hats, some molded out of crepe paper and glue, others pilfered from other men’s heads while they slept. Globs of dry sputum, nightsticks batting in feeble skulls, faces pockmarked with blacktop and yesterdays throw up. What were these men being sheltered from, certainly not spoil and privation, as these were all too common occurrence, a sort of impecunious insolvency, torment and misery, wooden boxes and shattered skulls.

One morning the man in the hat awoke abruptly, his heart racing, neurons firing like cherry bombs. He clutched the bedpost and waited for it to stop. It didn’t, it never stopped. Mr. Potato Head in sackcloth and Birkenstocks, feet conniving the void between agony and ecstasy: Skinnerian boxes, impecunious insolvency, torment and misery, sanctuary for the paranoiac and feeble. The man in the hat longed to see the beauty and genialness in things, not ugliness and want, which he saw against his better judgment, a judgment that wasn’t better after all. He yearned for joyful smiling faces with orthodox habits, teeth straight as arrows, hair glistening with gel, reconstituted from straw and fallow. He didn’t, he saw none of this, these things. He saw poverty and disfigurement, noses sharp as whittled sticks, eyes sunk deep into concave sockets, ears like curds, fingers bent into arthritic pretzels. He heard bawling children clutching threadbare dolls, heads shorn from necks, hair frizzed with constant thumbing, mothers with more ink on their bodies than words in the Bible, teeth chattering with inner cold. Corpse gaseous with cut-rate perfume, sanguine, freakishly pleasing, yet disturbing, insolvency, a discrepancy between what exists and what is dead, funereal wood. The antagonism and bitterness of savages, no way out of the circle, the enclosure, an imprisonment within one’s own body, a choleric transubstantiation of body, mind and essence, an existential famine. Everything is allowed, but nothing permitted.

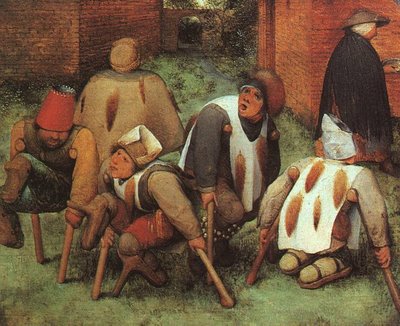

A man with a shamble leg, a deadweight he dragged like a cursor, ate nothing but birdseed and apple skins. He coexisted with animals and rain. He ate from birdfeeders and trash tins, fighting off crows and gulls. He drank from cesspits, hands cupped and drawn slowly to his mouth, a cockroach with a fleshy mandible.

One morning the man in the hat awoke abruptly, his heart racing, neurons firing like cherry bombs. He clutched the bedpost and waited for it to stop. It didn’t, it never stopped. Mr. Potato Head in sackcloth and Birkenstocks, feet conniving the void between agony and ecstasy: Skinnerian boxes, impecunious insolvency, torment and misery, sanctuary for the paranoiac and feeble. The man in the hat longed to see the beauty and genialness in things, not ugliness and want, which he saw against his better judgment, a judgment that wasn’t better after all. He yearned for joyful smiling faces with orthodox habits, teeth straight as arrows, hair glistening with gel, reconstituted from straw and fallow. He didn’t, he saw none of this, these things. He saw poverty and disfigurement, noses sharp as whittled sticks, eyes sunk deep into concave sockets, ears like curds, fingers bent into arthritic pretzels. He heard bawling children clutching threadbare dolls, heads shorn from necks, hair frizzed with constant thumbing, mothers with more ink on their bodies than words in the Bible, teeth chattering with inner cold. Corpse gaseous with cut-rate perfume, sanguine, freakishly pleasing, yet disturbing, insolvency, a discrepancy between what exists and what is dead, funereal wood. The antagonism and bitterness of savages, no way out of the circle, the enclosure, an imprisonment within one’s own body, a choleric transubstantiation of body, mind and essence, an existential famine. Everything is allowed, but nothing permitted.

A man with a shamble leg, a deadweight he dragged like a cursor, ate nothing but birdseed and apple skins. He coexisted with animals and rain. He ate from birdfeeders and trash tins, fighting off crows and gulls. He drank from cesspits, hands cupped and drawn slowly to his mouth, a cockroach with a fleshy mandible.

Thursday, June 01, 2006

mANGE and fECES

One-eyed dogs mange with feces, lynch tongues cirrhotic with fester and blain; he saw them everywhere, always. Perhaps, he thought, it was his own jaundice eye, a sightlessness that saw only the underbelly of things, dogs, humans and those straggled at the bottom rung of the ladder. The prison that exists within, as some suggest, is a lie, prisons are outward projections, social codes and mores, not bad genes or defective willing. Life is a random series of reoccurring events, many of which we have no control over, a psychotic repetition, duplicitous chicanery. He thought, the man in the hat did, that killing, dressing and eating a dog, one that had no chance of making a go of it, was a blessing for the dog, a way out of a life of repetition and meaningless abjection. The man in the hat, so he felt, was the patron saint of dogs, their benefactor, their profane Jehovah. He relieved them of their suffering, the mange and scourge of their lives’, ransoming them to a world of bounteous food, vast meadows and trampled sedge.

Things, the world of facts, are growing greener, olive drab, emerald, yellow-green, verdant, leafy, an iron oxide greenness. As long as greenness contains itself to nature, to trees and bushes, grasses and flowers, the man in the hat is content, as content as a discontented man can hope to be. Not gangrenous or purulent with ulcers, not fetid green, the augury of rotting and death, but a natural, macrocosmic green, a green that invites wonder and joy. A burgeoning greenness, an elephant frond green, petiole green, a lush forested green, a blissful enchanted greenness that enraptures the eye. Green upon greenness green, green.

Tungsten steel molded to fit round felon bone, a leg gone palsied and numb, deadened, insensate, a drag anchor shoehorned into place with a podiatrist’s speculum. He saw, the man in the hat did, a person tormenting himself down the sidewalk, the demilitarize zone, polder-stepping like a staggered calf. His mother, thought the man in the hat, probably took some antidote, a pillory to ward off vomiting and nausea, a parturition antitoxin. Caudal tails and miserly legs, wee stumps and hogs feet, dwarfed arms, his mother’s retching assuaged and corrected. He remembers a little girl from his childhood who had a hearing box strapped to her chest, an armamentarium of wires and coaxial cables, like spider’s legs, cinched round her back, held in place with a leather halter. A droning staccato, like bees hitting a windshield, emanating from her chest, a cybernetic ritornelle she controlled with toggle switch attached to the front of the box. The girl with the hearing box strapped to her chest heard no birds warbling, no children squealing with delight, tiny feet carrying them across paddocks shimmering with summer rain. She didn’t hear the cars whizzing past, tires fluting gravel onto the neighbor’s front lawns, lawnmowers spitting out stones and cog pins sheared through to white metal. All she heard was a low murmur, vibrations bouncing off her chest, straps caught in clothing too big for someone so small and inelegant. Perhaps, he thought, he could catch a tiny bird, a wren or a chickadee with frail, spidery wings, stomp it to death, panfry it with garlic, fennel and cold-pressed olive oil, wrap it in newspaper, and then offer it to her as a sign of his own empathy for her condition. Perhaps they could eat it together, perhaps on a picnic bench in the park, or behind the Dominion store behind the Waymart. He could unwrap it, spreading it out on the newsprint in front of her, then offer to cut it into ribbons small enough to clutch in her tiny nail-bitten hands. All things were possible, but very few permitted. Those few things that were allowed, tended to be so miniscule and farthing that it wasn’t worth of the bother of pursing them even were they placed in the upturned palm of one’s hand. The false impressions that reality left him with, forced the man in the hat to find other ways to make sense of what was so senseless and illusory. Trying to line up what one saw, experienced, felt and heard, was a lesson in the non-receptivity of his mind, his failure to stitch together the material, the phenomenal, with the categories and representations in his head. He allowed himself very little, and those few things he did, sparingly.

The man in the hat, he lived in a two-room walkup without a stove or icebox. He cold stored his perishables, which were few, on the ledge outside his bedroom window, and cooked beans and legumes on a hotplate he’d found in someone else’s rubbish. When he hadn’t the strength or wherewithal to stalk, kill and dress a dog, he ate at the homeless shelter, where they served tepid soups with squelchy vegetables and chowder that tasted like boiled fish roe. He ate with his back bent over his plate, alone, seated next to the fire door, his feet at constant shuffle beneath the tabletop. He dreamt of thirst quenching ales, lagers and stouts, of pastries folded one on top of the other, buttery crusts spilling over with mincemeat and fruit. He carved up red meat roasts, venison, mutton, and picnic hams in his sleep, boiling pots of potatoes, yams and rutabagas, skimming the froth from the simmer with a wooden ladle. He drank pear juice, sodas and applejack with an avarice broaching on madness, fingers clutching bottleneck and spout. He swigged cognac straight from the decanter, pearls of sweet, syrupy manna scalloping his tongue. He dreamt of caviar, black as road tar and crackers barbed with sesame seeds and cumin, spiced with chilies and minced pepper. He ate double over his plate, digging for scraps of boiled meat, a curd of potato, a yellow-tinged carrot, his feet jerking fretfully beneath the table. One time a man sitting across from him, his nose splayed diagonally across the tomb of his face, a cankerous tuber, spat up a mouthful of creamed corn, his dentures receding into the catacomb of his mouth.

Things, the world of facts, are growing greener, olive drab, emerald, yellow-green, verdant, leafy, an iron oxide greenness. As long as greenness contains itself to nature, to trees and bushes, grasses and flowers, the man in the hat is content, as content as a discontented man can hope to be. Not gangrenous or purulent with ulcers, not fetid green, the augury of rotting and death, but a natural, macrocosmic green, a green that invites wonder and joy. A burgeoning greenness, an elephant frond green, petiole green, a lush forested green, a blissful enchanted greenness that enraptures the eye. Green upon greenness green, green.

Tungsten steel molded to fit round felon bone, a leg gone palsied and numb, deadened, insensate, a drag anchor shoehorned into place with a podiatrist’s speculum. He saw, the man in the hat did, a person tormenting himself down the sidewalk, the demilitarize zone, polder-stepping like a staggered calf. His mother, thought the man in the hat, probably took some antidote, a pillory to ward off vomiting and nausea, a parturition antitoxin. Caudal tails and miserly legs, wee stumps and hogs feet, dwarfed arms, his mother’s retching assuaged and corrected. He remembers a little girl from his childhood who had a hearing box strapped to her chest, an armamentarium of wires and coaxial cables, like spider’s legs, cinched round her back, held in place with a leather halter. A droning staccato, like bees hitting a windshield, emanating from her chest, a cybernetic ritornelle she controlled with toggle switch attached to the front of the box. The girl with the hearing box strapped to her chest heard no birds warbling, no children squealing with delight, tiny feet carrying them across paddocks shimmering with summer rain. She didn’t hear the cars whizzing past, tires fluting gravel onto the neighbor’s front lawns, lawnmowers spitting out stones and cog pins sheared through to white metal. All she heard was a low murmur, vibrations bouncing off her chest, straps caught in clothing too big for someone so small and inelegant. Perhaps, he thought, he could catch a tiny bird, a wren or a chickadee with frail, spidery wings, stomp it to death, panfry it with garlic, fennel and cold-pressed olive oil, wrap it in newspaper, and then offer it to her as a sign of his own empathy for her condition. Perhaps they could eat it together, perhaps on a picnic bench in the park, or behind the Dominion store behind the Waymart. He could unwrap it, spreading it out on the newsprint in front of her, then offer to cut it into ribbons small enough to clutch in her tiny nail-bitten hands. All things were possible, but very few permitted. Those few things that were allowed, tended to be so miniscule and farthing that it wasn’t worth of the bother of pursing them even were they placed in the upturned palm of one’s hand. The false impressions that reality left him with, forced the man in the hat to find other ways to make sense of what was so senseless and illusory. Trying to line up what one saw, experienced, felt and heard, was a lesson in the non-receptivity of his mind, his failure to stitch together the material, the phenomenal, with the categories and representations in his head. He allowed himself very little, and those few things he did, sparingly.

The man in the hat, he lived in a two-room walkup without a stove or icebox. He cold stored his perishables, which were few, on the ledge outside his bedroom window, and cooked beans and legumes on a hotplate he’d found in someone else’s rubbish. When he hadn’t the strength or wherewithal to stalk, kill and dress a dog, he ate at the homeless shelter, where they served tepid soups with squelchy vegetables and chowder that tasted like boiled fish roe. He ate with his back bent over his plate, alone, seated next to the fire door, his feet at constant shuffle beneath the tabletop. He dreamt of thirst quenching ales, lagers and stouts, of pastries folded one on top of the other, buttery crusts spilling over with mincemeat and fruit. He carved up red meat roasts, venison, mutton, and picnic hams in his sleep, boiling pots of potatoes, yams and rutabagas, skimming the froth from the simmer with a wooden ladle. He drank pear juice, sodas and applejack with an avarice broaching on madness, fingers clutching bottleneck and spout. He swigged cognac straight from the decanter, pearls of sweet, syrupy manna scalloping his tongue. He dreamt of caviar, black as road tar and crackers barbed with sesame seeds and cumin, spiced with chilies and minced pepper. He ate double over his plate, digging for scraps of boiled meat, a curd of potato, a yellow-tinged carrot, his feet jerking fretfully beneath the table. One time a man sitting across from him, his nose splayed diagonally across the tomb of his face, a cankerous tuber, spat up a mouthful of creamed corn, his dentures receding into the catacomb of his mouth.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

About Me

- Stephen Rowntree

- "Poetry is the short-circuiting of meaning between words, the impetuous regeneration of primordial myth". Bruno Schulz

Blog Archive

-

▼

2006

(215)

-

▼

June

(19)

- mAN in hAT w/ bEGGARS7*

- jACKDAW7*

- bURGEE's mEDICINAL tONIC7*

- pEROXIDE and cLOVE oIL7*

- mEAT-eNDS ans gRISTLE7*

- 2@hAt7*

- tHOMAS' lIVER

- sHAmBLE-lEGgED mAN7*

- 2@9*hAT

- olD mAN, hAT, bUSTED lEG9*

- tHE hABERDASHER7*

- rEGIONS of the gREAT hERESY

- sKLEPY cYNAMONOWE

- cROCODILES and sANITORIUMS

- sKY pIMPS

- mAN28*

- dEMENTIA sOU'wESTER

- mAN2*7

- mANGE and fECES

-

▼

June

(19)

Links

- Windows Tuneup

- Apmonia: A Site for Samuel Beckett

- Bywords.ca

- Dublin Time and Day

- fORT/dAfORT/dA

- Google News

- John W. MacDonald's Weblog

- New York Freudian Society

- Sigmund Freud-Museum Wien-Vienna

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Taking the Brim _ Took the Broom

- The Blog of Amanda Earl

- The Brazen Head: A James Joyce Public House